Frank Dillon’s Legacy

Frank Dillon migrated to Hopkins County in Northeast Texas from Indiana in the mid-1880s. Soon after he arrived he married Mary (Molly) Corley, my father’s aunt. Aunt Molly, as my father and her other nephews and nieces called her, was the daughter of James “Squire” Corley, who rode with the First Alabama Cavalry. He was devoted to the memory of the Confederate General Nathan Bedford Forrest. Corley named his first son Forrest. Later, Dillon named one of his sons Forrest.

Dillon settled on a farm a half-mile from Squire Corley’s farm and a quarter mile from the county line between Franklin and Hopkins Counties. In anticipation of a sizeable family, he built a house with four bedrooms. He also built a blacksmith shop and a building that housed a general store. James Corley was a partner in the operation of the grocery. Dillon also built a blacksmith shop near the store building. He and Corley built a cotton gin on a spot near the creek that ran through the Dillon place. At the same site they built a kiln so they could make their own bricks for chimneys and other uses. The bricks in the two chimneys in the house Frank Dillon built came from this kiln. He applied to the U. S. government and was granted the right to operate a post office, which existed for approximately ten years in the early 1900s. The mail was delivered from the Saltillo train by a carrier in a horse-drawn buggy. It was Dillon’s hope that the community would become a growing town.

Dillon settled on a farm a half-mile from Squire Corley’s farm and a quarter mile from the county line between Franklin and Hopkins Counties. In anticipation of a sizeable family, he built a house with four bedrooms. He also built a blacksmith shop and a building that housed a general store. James Corley was a partner in the operation of the grocery. Dillon also built a blacksmith shop near the store building. He and Corley built a cotton gin on a spot near the creek that ran through the Dillon place. At the same site they built a kiln so they could make their own bricks for chimneys and other uses. The bricks in the two chimneys in the house Frank Dillon built came from this kiln. He applied to the U. S. government and was granted the right to operate a post office, which existed for approximately ten years in the early 1900s. The mail was delivered from the Saltillo train by a carrier in a horse-drawn buggy. It was Dillon’s hope that the community would become a growing town.

Aunt Molly Dillon died some twenty years after her marriage to Frank. They had eight children. A year later Frank married a widow, Donna Richey, of the Pine Forest community. Donna bore three children during her second marriage. For some reason the marriage failed. In a West Texas weekly paper dated 1927 there is a record of Frank Dillon’s death. His remains were buried in McAdoo, Texas, three hundred miles from the place he poured his soul into. In 1926 my parents and my two sisters moved into the Dillon house. Five years later I was born in the main bedroom.

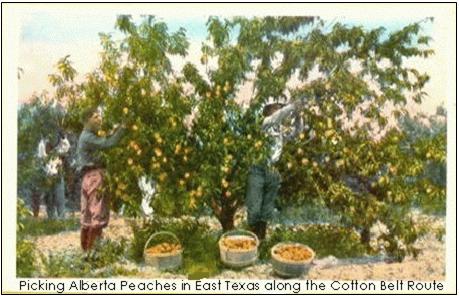

Years after Frank Dillon moved away there were benefits for those of us who occupied the farm he developed. By the time I can remember, several of the Elberta peach trees in the orchard he planted were still bearing fruit. The taste of a fresh, succulent peach from the orchard still lingers. With help from other adults in the family, including my grandmother (Theodosia Corley Cowser), each summer my mother peeled and preserved many of the peaches from the orchard. Some were pickled in sugar syrup with cloves added to the mixture. Some of the peaches were diced and dried in the summer sun that heated the tin roof over the side room.

Years after Frank Dillon moved away there were benefits for those of us who occupied the farm he developed. By the time I can remember, several of the Elberta peach trees in the orchard he planted were still bearing fruit. The taste of a fresh, succulent peach from the orchard still lingers. With help from other adults in the family, including my grandmother (Theodosia Corley Cowser), each summer my mother peeled and preserved many of the peaches from the orchard. Some were pickled in sugar syrup with cloves added to the mixture. Some of the peaches were diced and dried in the summer sun that heated the tin roof over the side room.

One apple tree stood in the pasture adjoining the peach orchard. The apples it produced were firm and tart. My mother made delicious apple cobbler when the apples were in season. She would sprinkle butter, cinnamon, and brown sugar on the crust.

The blackberry vines Frank Dillon planted along the fence row separating the cotton field from the orchard were still producing when I was a child. The berries in their first stage were green; then they turned a bright red. When they turned a dark violet, we knew they were ripe. They were delicious right off the vine, and my brother and I ate our share as we picked the berries on mornings late in May. Our mother made jelly and jam and cobbler from these berries.

The blackberry vines Frank Dillon planted along the fence row separating the cotton field from the orchard were still producing when I was a child. The berries in their first stage were green; then they turned a bright red. When they turned a dark violet, we knew they were ripe. They were delicious right off the vine, and my brother and I ate our share as we picked the berries on mornings late in May. Our mother made jelly and jam and cobbler from these berries.

These remarks are a belated tribute to Frank Dillon to whom I owe a debt because his efforts years before I was born gave me and the others in my family some delicious and nutritious treats.

These remarks are a belated tribute to Frank Dillon to whom I owe a debt because his efforts years before I was born gave me and the others in my family some delicious and nutritious treats.

.

The Cotton Belt Route Railroad printed this poster showing some of the fruits they hauled out of Hopkins County