Cooking Ribbon Cane Syrup*

By R. L. Cowser

My father, who is approaching his eighty-seventh birthday, is a past master at cooking ribbon cane syrup. So far as can be determined, he is one of the last survivors who cooked ribbon cane syrup in the old-fashioned, traditional way. But in order for the cook to have the product, a growing season of several months was required. The selection of soil, of the cane itself, and the uses that the cane, its juices and by-products could be put to all form an interesting lesson in what today would be called conservation. The best type of soil for growing ribbon cane is light, sandy bottom land.

One acre of ideal land could produce on the average about three hundred gallons of syrup. This light, sandy soil produced a brither, clear, and sweeter product. Since the cane required a long growing season, the growers would plant it in early spring and not cut it before the first killing frost.

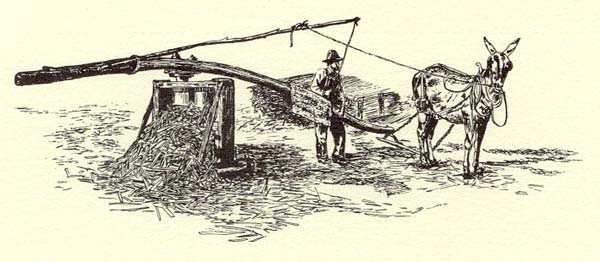

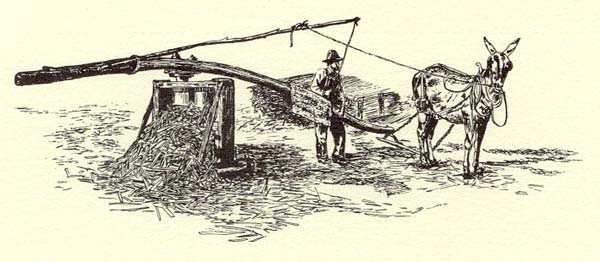

After the cane had been brought to the syrup mill, the juice was mashed out of it with larger rollers; these large rollers, sometimes called crushers, were a part of a machine whose power originated from a pair of horses or mules. In some cases, only one animal was needed. The horses or mules pulled the rollers by walking continually in a wide circle. The animals were attached to a long pole which was fastened to a shaft which in turn pulled the rollers. The raw cane juice was caught in a large barrel with a pipe in the bottom of it. Through the pipe the juice was siphoned off into a ten-to twelve-foot flat pan. The juice was then heated with cord wood that had been placed under the pan in a furnance made of brick with clay and post oak soil used for mortar.

The pan was of unique design. It had dividers all the way down it, from one end to the other. These dividers would extend from the right side of the pan to about two inches from the left side. Then the next divider divider would begin on the left side and extend out in the pan as the other one did from the opposite side. As the raw juice wound its way, in serpentine fashion, down to one end of the pan, enough time had passed for for it to have cooked and to be ready to be siphoned off as syrup.

The cook would use a wooden spatula occasionally to aid the flow of the boiling cane juice. Seven to ten gallons of raw juice boiled down to one gallon of syrup. All refuse and waste from the raw juice came to the top while the juice was cooking. This waste was removed by the cook who used a "skimmer" made of a fine wire sieve attached to a long handle such as one from a broom. The required cooking time was approximately one hour. Then the new syrup was drawn off and placed in large containers to cool before it was poured into jugs or buckets, usually of one gallon in size, and then the delicious, sweet syrup was ready to be sold or eaten.

Cane juice, however, provided more than just syrup for human consumption. Its uses were various and valuable to the farmer and hog raiser. The juice rich in sugar, could be formed into "beer" in about nine days' time. And by inserting a cork with a coarse twine string suspended from it into a quart canning jar, rock candy could be formed. For the least affluent families to use this rock sugar for cooking purpose was not uncommon. The ten percent sugar content of the juice crystallized and formed rock sugar around the string, which was easily removed from the jar and the cork.

The by-products of the cane also had practical uses. The pulp was stored, and cattle could feed on it all winter. The waste skimmings were often saved and used for hog feed. The ingredients in the waste helped to fatten hogs quickly, and it also made them sleeker with shinier coats.

In additon to the cook, four other helpers were required or needed. These five people could produce about one hundred gallons of syrup per day if they worked from dawn to dusk; one hundred fifty gallons if they worked till midnight., as my father often did. The custom of cooking ribbon cane syrup in the old-fashioned, traditional way practically ceased in East Texas during the early 1950s. If it continues, no more than one or two syrup mills are still operating. The few mills which today are producing syrup use tractors for their "horsepower," rather than mules or horses; the former are not easy to find. However, those of us who have watched this traditional process will not forget the atmosphere of expectation and excitement which each autumn brought just before the big frosts set in. We were anticipating having on a chilly morning a breakfast of fresh pork, home churned butter, and homemade hot biscuits flavored with fresh ribbon cane syrup. What a treat!

_________

R. L. Cowser, son of Roy Cowser and brother of Robert Cowser, grew up on a farm five miles south of Saltillo. From 1963 until his death in 1987, he served as Chair of Modern Languages Department of Wharton County Junior College, Wharton, Texas. Roy Cowser, the father, cooked syrup at his own mill in the 1930s and then for several other cane growers south and east of Saltillo.

*This article was published in The Kentucky Folklore Record (Jan. Mar. 1978)