Summertime

When I was a boy the first sign that summer was just around the corner was when it warmed up in late spring and I got to go barefoot for the first time that season. The grass would tickle my tender feet when I first walked on it without shoes. The texture and feel of warm gravel to my feet was also a new sensation. Barefoot, I felt I could run faster than with shoes. My feet felt as if they had been set free from months of bondage . . . which they had.

After my feet had been liberated, the next emancipation was from school. Just as I would be anxious for school to take up in the fall, I was equally as anxious for it to end in late spring. When I would think of the coming of summer, visions of swimming, eating watermelon, and fishing were some of the first things that came to mind.

Texas being arid, or semi-desert, it jumps from warm to very hot fast; the lazy days of summer are hot and dry. Water and other moisture-laden items take on important meanings. You drink lots of water, and locals can tell you which well or spring has the best tasting water. If there were a regional drink other than water in the Southwest, it would have to be iced tea. Drinking cool fresh water or iced tea, eating watermelon, sitting in the shade, licking an ice cream cone, and swimming are all pleasant ways for Texans to beat the summer heat. Evolutionists touch on something when they say we came from the sea and will always crave water.

We kids swam in the nude, and we swam everywhere around the little town of Saltillo . . . railroad reservoir . . . railroad tank . . . muddy stock ponds . . . Stout's Creek. The railroad reservoir was just east of town alongside the Cotton Belt Railroad tracks. It was probably dug so as to keep ample water on hand to fill the water tank across the tracks from it, where steam locomotives pulling cars stopped to fill up. A large part of this reservoir, which occupied maybe 10 acres, was covered with Lilly Pads. Every kid when growing up was cautioned about swimming near or in Lilly Pads, being told that if you were not careful you could get entwined in the vines and drown. Plenty of water moccasins and turtles also shared this little lake with the Lilly Pads. The lake was deep, and there were few gradual slopes leading down from the water's edge. One had to be a pretty good swimmer at the reservoir, otherwise you sat on the bank a lot.

There was much clowning around in the water . . . last pickle on the table . . . spewing water like a whale . . . water fighting . . . throwing mud balls. On some days we would ride our ponies to the railroad swimming hole, and make them swim with us by jumping them off into the water. We usually rode bareback, so there wasn't much riding gear you could get tangled up in. The ponies were reluctant at first to jump off into the water., but a lot spurring with one's heels, verbal coaxing, and moving the reins from side to side caused them to take the plunge. Once in the water you would slide off your pony's back and grab hold of its tail and let it drag you through the water; like a half-submerged submarine, as it swam to the opposite shore. When the ponies finally made it to the other side of the lake, some of them floundered (or thrashed about) because they had a hard time scampering out on the slippery clay bank. Once on land, they shook the water off, and seemed to enjoy the swim as much as we did on a hot day.

Across the track from the lake was a large Cotton Belt Railroad water tank, from which, as I have said, steam locomotives took on water. This tank was about 40 feet in diameter and stood about 65 feet tall. It had a ladder on the outside and one on the inside. Talk about a nice swimming hole . . . this was the closet any of us had ever gotten to a real built pool. When the tank was nearly full, we would see how far we could descend in the water, holding onto the ladder. You would reach a point where the pressure made you feel strange and your ears would start popping. It was fun swimming in the tank, but when a train would stop to get water, we were quiet as mice. The railroad didn't like for anyone messing with its equipment or property. The formal name of the railroad was St. Louis & South Western Railway, which represented a sort of mysterious authority that resided elsewhere, so we were leery of it.

Sometimes we would swim in a muddy stock pond. The surface of these ponds in the summer was warm, and got progressively cooler, deeper down. There were crawdad holes around the edges of the ponds. They also had their fair share of water moccasins, frogs, and turtles. The bottoms of the ponds were of soft, murky silt, that came up to mid-calf on your legs.. Willow trees tended to grow around these ponds and the water moccasins would lie on their branches as if sunning themselves. At times an occasional piece of cow dung could be seen floating on the water. Nothing ever caused us to think twice about swimming in these watering holes.

In his book, Yesterday in the Hills, Floyd C. Watkins tells about working all day in a hot, sunny hayfield in the Piedmont Hills of Georgia: when dusk came and the sun would slip below the horizon, the hands would load a wagon with hay and head for the house. He said lying on the hay in the wagon, slowly rolling toward home, was something you would have to experience to appreciate: the pure relief on a bed of fresh hay after a hard day's work. Similarly, I can recall swimming most of the day and then going home half starved and eating a hunk of cold leftover cornbread with a couple of slices of onion; the most incredible, satisfying food I could ever imagine.

Fishing was just as about as much fun as swimming in the summer. Around East Texas in the 1930's it wasn't a complicated undertaking to go fishing. All you needed was a pole, a line, and some worms. If you were really optimistic, you took along a gunny sack to tote home all the fish you thought you might catch. We caught mostly perch in the stock ponds. They were hyper little fish that would grab your hook and take off as though they were going to leave the pond; it was easy to pretend you had a fierce, fighting fish on your line. The perch were small, took forever to clean, and were most tasty. They were a nice change to our regular diet. For catfish, we went to Stout's Creek just west of Saltillo. A catfish is altogether a different sort of fish on your line. He swallows your hook and slowly pulls it and the cork toward the bottom of the creek. As with perch, it was very exciting catching catfish. You always wondered between the time one swallowed your hook and you pulled it out of the water, just how big it was. Unlike the perch, catfish had to be skinned, rather than scaled. This was a skill all country boys eventually mastered--a rite of passage.

Thunderstorms go with summer in Texas, like ham with eggs. They can be awesome: dark clouds form slowly in the sky--as a storm builds, with much lightening and cracks of thunder. These storms are the most intense on really hot blistering days, as if they have a job to do in cooling things down and settling the dust. They move slowly across the terrain. On hearing the sharp cracks of thunder as a storm gets closer, gun-shy dogs whimper and howl, as they don't know quite what to do, and try to find a place to hide. The first drops of rain are welcome. They sizzle on hot tin roofs, bricks, and the bodies of cars. The air smells different . . . pungent . . . as if someone had spit on a hot stove. The rain picks up, blowing in sheets. The ditches start to run with water. if the storm lingers, or another rain comes along the next day, the creeks begin to rise. When it really pours, Stout's Creek gets a cleansing. After one of these rainstorms has passed through and the sun is shining again, it is like a new day -- fresh and cool. Every kid in my time would go out to wade in the flowing ditches.

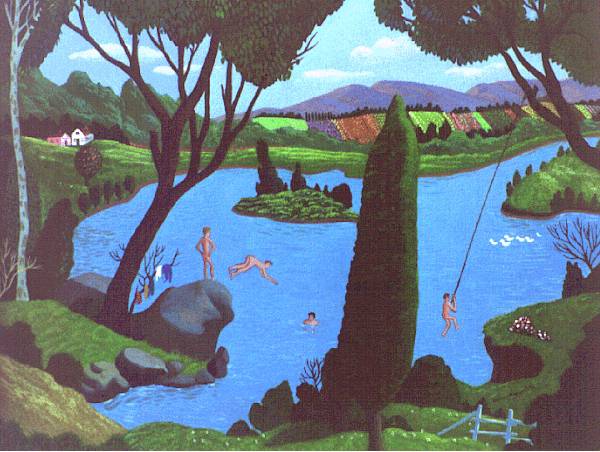

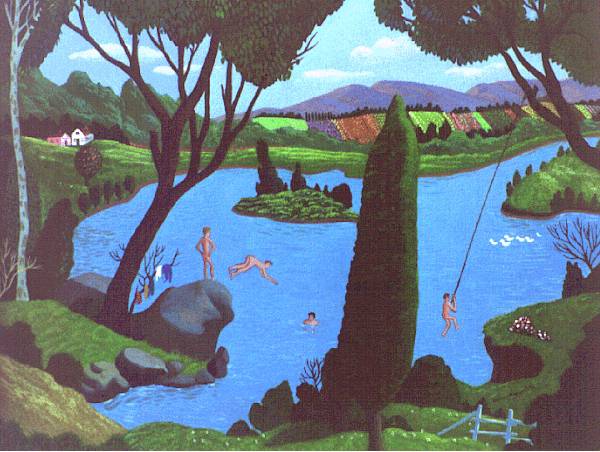

One of the happenings of summer everyone looked forward to was called "all day singing and dinner on the ground." This event usually took place at a nearby church in July. My favorite was at Greenwood, Texas, which was a few miles south of Saltillo. The food wasn't really on the ground, as it might have been in the old days, but on plank scaffolds built between trees. These makeshift tables were loaded with food of all kinds. There was one whole table with nothing but desserts; pie, cake, pudding , cobblers, ice cream, watermelon, and other sweets. Once the word went out; that the food was ready, I headed straight for the dessert table. As the people ate, candidates for election to public office circulated amongst them, shaking hands, and passing out their cards. Near the church at Greenwood was a stream called Poor's Creek. It had the best swimming hole around the area, complete with a rope for swinging off the bank and into the water. Once all of us boys had our fill of food, we headed for the swimming hole. The admonishment: "don't swim too soon after eating", meant absolutely nothing to us.

As summer wore on, bored of routine, we would strike out on a new adventure that sometimes led to mischief. One day another boy and I rode our bicycles out US 67 to a sugar cane field a few miles east of Saltillo. Arriving at the cane patch, we laid our bicycles down on the side of the highway and entered the patch, We thrashed around breaking down stalks until we found the ones we wanted. Then we peeled back the outer layer of the stalk to get at the pulp. We then chewed the pulp to get the sweet juice. After a while, we tired of this and returned to our bicycles. They were gone . . . nowhere to be seen.The owner of the cane field, who lived across the highway on the top of the hill, had came down the hill and taken our bicycles back to his house and put them inside. He was sitting on the front porch, probably relishing the moment when we figured out what happened to our bicycles. Jesse Stuart in his book, The Thread that Runs so True, said one of the most difficult things he ever had to do, which his father insisted on, was to go down a long lane to a farm house, knock on the door, and when the owner answered it, apologize to him for pilfering apples out of his orchard. And like Jesse, we too had a sorry little mission to carry out as we slowly ascended the hill to plead for the release of our bicycles. The man played with our minds and our emotions a while before finally handing over the bicycles.

As I got older, the summers started losing some of that Currier & Ives character of boyhood. In addition to regular chores, I was expected to start doing some man's work. Cotton was still king in the South and southwest before World War II, so picking it and pulling its bolls fell into the man's work category. It was the worse kind of work to be shanghaied into: hot and boring. The day never seemed to end, and progress was measured in very small amounts. Boys tried to make the ordeal more pleasurable by throwing cotton bolls at each other, lying on their cotton sacks, visiting the water jug often, and other such non-productive diversions.

Keeping with serious character building, I spent most of one summer working for a sharecropper in his cotton patch. The work was practically from sunup to sundown. My job was to go up and down the long rows of young cotton plants behind a horse pulling a plow, called a "Georgia Stock," tilling the soil. The Georgia Stock had a large, V-shaped blade that cut the grass and weeds as it moved under the surface of the soil. The sharecropper used a team, a horse and a mule, that pulled a cultivator that also worked the soil and cut the weeds and grass. A mule can take heat and work better than a horse. The sharecropper had worked two horses to death teamed with his mule in as many years.

I, also, worked the harvest on the farm where we lived one year. Horsepower did most everything. The grains, oats or wheat, were caught in gunnysacks from the threshing machine, loaded onto wagons and hauled to the barns. My job was to get inside the grain bins and empty the sacks as they were handed in. It was a dirty, hot, itchy job. At the end of the day I would cough up black sputum. To cool myself down, and cleanse my body of chaff and grime, I took a swim in the pond about dusk. It was a welcome reward for the long day's work. The most fun of the day came when some field hand would pick up a stack of wheat or oats with a pitchfork to throw it upon a wagon and find a snake had taken refuge in the fodder. Everyone would laugh at how quick the worker would scramble to get away from the snake.

If there was one thing that approached shrine status in the summertime, it would have to be an ice cream parlor. The drugstore in Saltillo was a combination post office, pharmacy, and dime store. It was operated by Rau Arthur. The post office occupied a small area in the back of the building. In another area was the soda fountain and ice cream parlor. The parlor had the familiar little round wrought iron tables with marble tops. The tables were complemented with wrought iron chairs with little round seats. Swung from the ceiling over the parlor, large electric fans turned slowly. The fountain served floats, sundaes, malts, cherry cokes, ice cream in a dish, ice cream cones, and other delicious things. Eating ice cream in the summer is an experience you try to prolong as long as possible. There was something about the old time ice cream parlors with marble topped tables, the cool of overhead fans, and the smell of milk and ice cream that evoked pure hedonism in one. It still does today, although it is becoming increasingly difficult to find an ice cream parlor that has the aura of the old-fashioned ones..